Why Libertarians Don’t Get Along, Part 2

Doctrinaire debating ourselves to death

There is a joke in libertarian circles:

Q: What is the difference between a minarchist and an anarchist?

A: About six months.

The deepening of my classical liberal views, from mainstream conservatism to austere libertarianism, required a great deal of study, conversation, and mind-bending exploration. All told, it took about 15 years. The last portion of that journey, however—from minarchist to anarchist—really did take just about exactly six months!

There is definitely something to that joke.

Once I made that final swim to Anarchist Island, a whole new journey had begun. What exactly had I become? I had to study more. And what happened next is pertinent to our discussion today.

Being a sociable member of a social species, my first stop was to seek out others like me—in this case, in an online group of anarcho-libertarians. What do you think happened next?

Did they say, “Welcome, friend” and express pleasure at adding one more person to a belief system that—let’s face it—isn’t shared by a whole heck of a lot of people? Nope.

Instead, the first person I encountered corrected me for improper use of an abstruse piece of terminology, and the second disagreed with the first. All within the first five minutes.

And there it was: the division and infighting I had heard was so common in libertarian circles. I couldn’t have had a more striking demonstration.

I’m a splitter, you’re a splitter…

In Part 1, we explored splitterism (also known as sectarianism)—the phenomenon whereby ideological and political movements experience internal division over minor differences of opinion on principles, doctrine, rhetoric, or tactics. We identified six general reasons why groups centered on philosophical or ideological principles are especially prone to internal conflict and fracturing—often over very minor variations in an otherwise shared set of beliefs.

Libertarians are frequently lampooned for this tendency, and for good reason. But the truth is, the broader freedom movement—conservatives, libertarians, and anarchists—is prone to it, and it is not helping the cause that we broadly share: the freedom and independence of the human person.

If you are a libertarian, and you reacted with a burst of frustration at my inclusion of conservatives in the freedom movement…

If you are a conservative, and you think libertarians are weird and dangerous…

If you are an anarchist and you think that no one—including fellow anarchists!—is sufficiently pure or precise in their views…

you may be contributing to this destructive and counterproductive phenomenon.

I say that with respect and a spirit of fellow feeling. I also say it with a measure of accountability, for I too have contributed to this climate at times.

This is a problem we should try to solve, or at least mitigate. I will seek to justify my claims below, and then complete that justification, and offer a few ideas for solutions, in upcoming installments.

Doctrinaire Details and Dire Rivals

Conservative, libertarian, and anarchist are just the top-level categories—three modern manifestations of a classical-liberal substrate. Many divisions, especially within libertarianism, run much deeper.

None of the following debates can get the treatment they deserve in this short space. Here, however, is a brief summary:

Minarchists vs. anarchists: Fighting like siblings

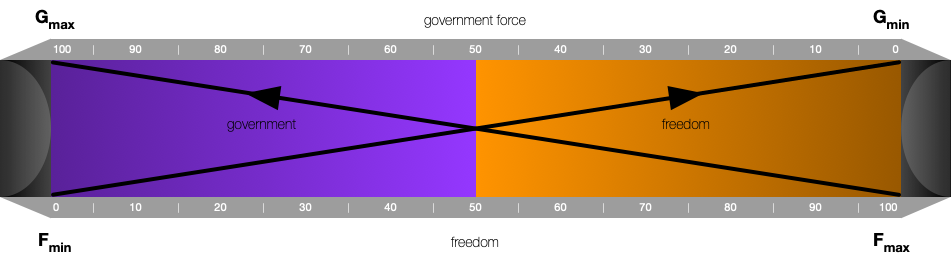

In one sense, these two are the closest. If we define a continuum from 100 percent involuntary governance (zero freedom) to the extreme left and zero percent involuntary governance to the extreme right (Figure 1), then we can (very roughly) fix the size of a minarchist government at five percent or less. This means that to the extent such things can be quantified, minarchists and anarchists are separated (in the amount of involuntary governance they want) by less than five percent.

And yet, the realizations that cause one to bridge the gap from that five percent to the zero percent of full anarchism are so fundamental that the gap, while short in linear distance, feels very deep. You can easily step over the rift to the other side (hence the truth of the “about six months” punchline), but most aren‘t looking at the short linear distance. Instead, minarchists and anarchists are each standing on their side, gazing down into the rift’s seemingly chasmic depths. And then occasionally looking up to glower at each other.

Personal note:

Having crossed that gulf myself, I entirely understand why we do this. But we should not do it! A little friendly debate is fine, but it is strategically foolish to treat our closest ideological allies as dire rivals. You may disagree with your siblings on this or that, but at the end of the day, they’re still your siblings. And that matters…through thick and thin.

Thicks vs. thins

As much as I can, I try to stay out of such sectarian disputes. As such, I only became aware of the “thick” vs. “thin” debate comparatively recently. In essence, the distinction is this: Thins focus on the core ideas of libertarianism: the nonaggression principle, property rights, and the centrality of consent. Thicks insist that a libertarian ought to apply those principles to a broader menu of concerns—from feminism to family values, depending on who you ask.

Personal note:

I get that there are sophisticated nuances underlying this debate, but at the end of the day, it is thick-headed (and thin gruel) to fight about such things.

The thins are largely correct in their belief that if first principles are properly followed, the rest of these issues will improve organically. But if thicks want to put an extra focus on this issue or that, why not? As long as they are truly applying libertarian principles in those pursuits, we can wish them Godspeed. (And if they are not applying libertarian principles, and instead want to deploy government force to “solve” these issues, then they should stop calling themselves libertarians, thick or otherwise.)

The thins, for their part, are keeping the flame of first principles burning hot and bright. We should thank them for that, not assail them for a lack of focus on some particular issue.

If everyone focuses on their interests, good things will get done. And getting things done is what we want, right? RIGHT?

Pragmatism vs. purism

This is a perennial debate for ideological and political movements. Should adherents compromise in order to make incremental gains or hold fast to pure principles, even if it means making less progress?

This question is especially thorny for libertarians, given their general oppositional disposition towards government. Should libertarians work within a system we oppose, in hopes of making marginal improvements? Or does continued participation validate that system and serve as a kind of trap?

There are no easy answers. Yet one thing is for sure: it is entirely counterproductive for those who have chosen one path to assail those who have chosen the other. Everyone doesn’t need to be doing the same thing.

Personal note:

There is a third option: a deliberate and purposive plan to make incremental progress outside the system. I hope to complete my presentation of such a plan in 2026.

Consequentialists vs. deontologists

Consequentialists justify their libertarianism primarily on the grounds that libertarian ideas produce superior results for individuals, societies, and overall human flourishing. Milton Friedman justified his brand of moderate, Chicago School libertarianism on those grounds. His son David justifies his anarchocapitalist views in the same way.

Deontologist is an abstruse term of art for someone who justifies his views on moral grounds. In our context, this means someone who believes that individuals have inherent natural rights that ought to be respected by others, including by agents of any government. Murray Rothbard is most famously cited here, but there are many others.

Personal note:

I am a natural rights guy. Setting aside personal things like my love for family, I do not think there is anything I have believed more strongly in my entire life than in the existence of inherent natural rights—rights that absolutely preexist any government.

But I am not going to argue with my consequentialist fellows over this. They are correct: classical-liberal principles really do produce better results! That is good enough for me, and I am happy to collaborate with them on these grounds.

Think of what might happen if we all looked at each other, shook hands, and said,

“We are allies in a cause far greater than ourselves.”

Doctrinaire-detailing ourselves to death serves no valuable purpose. Does a discussion of consequentialism vs. deontology bore you? Good! It is fine to understand the contours of the debate, but we should never allow ourselves to get lost in it.

Left vs. right libertarianism

At FreedomFest 2021, emcee Dave Smith noted, in a comedic way, that the attendees included libertarians, anarchists, conservatives, and Republicans, and that there “might even be a couple of Democrats here.” He was expressing the reality that, ideologically and philosophically, leftism is the opposite of libertarianism. As such, few leftists are likely to attend such a conference.

The underlying truth of Smith’s point is difficult to refute:

From a consequentialist standpoint, the lessons of history are clear. The ideas of leftism tend to lead to economic failure and a diminished latitude for freedom and innovation.

From a deontological standpoint, little could be more inimical to the natural rights of the human person than to use force to turn some into the means to others’ ends…and that is leftism’s stock and trade, as we will discuss in detail in Part 3.

When the ideas of leftism are applied fully, the result is soul-crushing oppression and mountains of corpses. Cries of “That wasn’t real socialism” will not avail. It happens every single time, in every single country and culture in which leftism is fully imposed. That isn’t acceptable from a consequentialist or a natural-rights perspective.

All of that having been said, left libertarianism is a real thing. Left libertarians emphasize some of the same themes that modern leftists do—racism, social hierarchies, labor issues, and so forth—but do it from a libertarian perspective, seeking to solve such issues without state intervention.

Personal note:

One of the common threads among many left libertarians is anti-propertarianism. In other words, mirroring the orthodox left, some left libertarians question whether individuals have a right to own certain kinds of property. Some even oppose all property ownership outright.

Given the centrality of property rights to most strains of libertarian thought, this is difficult to reconcile. Property ownership is a direct and necessary outgrowth of self-ownership, and it is hard for me to imagine denying self-ownership while still calling oneself a libertarian. However, they do call themselves libertarians, so I will listen to what they have to say. There is room to find common ground even among those who disagree on many things.

The gap between left and right libertarians is significantly larger than the rest of these divisions, and it might be easier and wiser to bridge the smaller gaps first. Nonetheless, in the spirit of comity and a pursuit of solutions, I am happy to work with anyone toward mutual strategic objectives.

Individuals in search of clarity

In Part 1, we discussed some psychological and practical reasons why groups—especially those with ideological, philosophical, or political bases—are prone to this type of division. Yet there are further reasons why libertarians, and others in the freedom movement, are especially susceptible.

Independent by nature

All classical liberals, to one degree or another, hold the view that the individual is the fundamental unit of moral concern and analysis in society. We recognize the reality that groups do not think, choose, or feel—only individuals do. We understand that there is no “general will,” and any claim to the contrary must be made, and forcibly imposed, by some small group of individuals. Rousseau gave up the game when he told us that non-conforming individuals will have to be “forced to be free.”

It should come as no surprise, then, that the same people who recognize the evils of collectivism would be individualistic by nature.

Libertarians are not generally known as joiners (and are sometimes lampooned as being “autistic”).

Conservatives cherish rugged individualism.

Anarchists add in the profound conviction that no involuntary government is morally permissible at all.

One may reasonably expect such people to be more fractious. Some will even be immediately suspicious of any coordinated action…even when it is going well.

The quest for crystal clarity

The freedom movement isn’t just any old movement. We are the people charged with defending the rights and freedom of the human person against all forms of tyranny.

We live in a world where many have an instinct that their own freedom matters, but don’t quite understand why that is or what to do about it. It is also a world in which plenty of others are far more interested in security and ease, even if it comes at the cost of their own freedom, or that of their fellow humans.

We live in a world that has languished for millennia under statist control. A world in which some sort of hard or soft tyranny has been the rule rather than the exception. We are up against the architects of tyranny, and their enforcers and operatives. We are up against the cheerleaders for tyranny, those who are apathetic about it, and those who believe that nothing but tyranny is possible for mankind. We are up against all those who want the government to extract resources from some and give them to themselves or others.

And all of these, to one degree or another, fear or hate us.

Even when we include all stripes of conservatives in the freedom movement, we are still not any kind of majority in human society. And yet we—and seemingly we alone—understand the threat and the need.

Is it any wonder, then, that we are so concerned with getting it right? That we would search, and search, and search some more to find ironclad justifications for our beliefs? This is precisely the sort of quest that produces endless discussion and debate—and that, all too tragically, leads to division, ideological gatekeeping, and paralysis.

Such a quest also attracts intellectuals, and many intellectuals are perfectly content to debate endlessly, even if nothing practical ever gets done.

I do not doubt that these sorts of problems plague other movements as well. But I am not concerned with those movements. I am concerned with ours.

At any one moment in history, those who are fighting for the true freedom and independence of the human person are drastically outnumbered and outgunned. The primary reason that the cause of freedom continues to be pursued is because of the efforts of people who genuinely get it.

Somehow, some way, we must overcome these divisive tendencies. History doesn’t care about our purity tests. It will remember whether we defended freedom when it mattered. Which side of that ledger will you be on?”

Stay tuned for Part 3.

> Being a sociable member of a social species, my first stop was to seek out others like me—in this case, in an online group of anarcho-libertarians.

Is the problem not the freedom-advocacy folks, per se, but that such people tend to "meet" online rather than in the person?

There are enough republicans and democrats that they actually know one another in their towns and maybe at higher level organizations, too. But freedom advocates don't have such in-person organizations. Even before the internet, much of freedom advocacy was done remotely through reading articles and books. That's not really a *social* movement, even though the word "social" is in the term "social media."

One of those pieces that, ideally, is worth the read and will bring some of us from different sectors of libertarian together.

For me, I’m Rothbardian, but the way I ultimately see it: any brand of libertarianism is better, way better, than the mainstream leftist agenda.

I’m not gonna care if there’s minute differences, or even moderate differences, in our thinking.

Can we all agree that the mainstream left is a problem and needs to be phased out through an ideas revolution?

That’s something, common ground, all libertarians should stand on.