It is said that the three topics one should avoid in polite company are religion, politics, and money. And with good reason. If you are looking to inject strife into an otherwise friendly conversation, those are all excellent choices.

Yet money is important. We frequently speak of money as if it is bad, but in its basic form, it represents a huge portion of human activity. It represents survival.

Indeed, in its basic form, it is a good thing.

Money Is Human Action

You are standing on a ball of rock orbiting a giant ball of hot gas. As balls of rock go, ours is quite nice. It provides everything you need to survive and thrive.

But it doesn’t just hand it to you. You must think, choose, and act toward your own survival. And if you fail to do so, that ball of rock isn’t going to step in and save you.

So you do the things of survival. You find the food. You build the shelter. You make the tools. And you barter with others who are doing the same. But eventually you discover that barter gets complicated when you make shelters as a trade and all you want is a single egg from the chicken guy.

Money—an agreed-upon means of exchange—solves this problem (and several others). Money, in its basic form, represents human labor and ingenuity. It facilitates survival. It facilitates thriving. It is good.

So why does it feel so evil?

The Persuader and the Coercer

In addition to its other merits, money also represents human cooperation and peace. It allows a person to say,

Hey, instead of taking that thing from you by force, how about I trade you something for it?

That too makes money a good thing. The money he trades for the thing he wants represents something productive he did in the past. He provided labor, ideas, goods, or services to someone else who gave him money for it. Then he gives that money for the thing he wants.

Except…not so fast. Not everyone gets their money that way.

Some steal it. Some use trickery to obtain it. Some have a lot of it already, and use the power that accompanies wealth to extract even more of it—sometimes in ways that aren’t entirely ethical.

Money gets you things you need in order to survive and thrive. But there are, in essence, two ways to get that money: persuasion or coercion.

You can create something that other people value and then peacefully persuade those others to give you something you want in exchange. Or you can use force or trickery to extract money and other things of value. Make or take. Trade or extract.

Most exchanges of money are persuasive. The vast majority of private exchanges are peaceful, positive, and win-win. And yet, because of our natural revulsion toward bad behavior, and our innate negativity bias, we feel the immoral extractions of money far more keenly.

The Gini Coefficient

Social science now has fairly definitive evidence that human beings have an deep, innate, evolved distaste for inequality. When someone has more—especially a lot more—it can have a visceral effect on others. People tend to feel the gap quite keenly.

This leads to charges of “greed” and cries of “how much does one person need?” And maybe the rich person is question really is greedy or money-obsessed. Those are unattractive traits, to be sure.

Yet, if the rich person used persuasion—if he got rich by providing things that people want, without using force—then has he really done anything bad…no matter how much he has?

Who is the truly greedy—the person who works for what he has, or the person who envies what another has and takes it?

Crony Capitalism

Sadly, some fabulously wealthy people have used a kind of force.

Governments give favored businesses special status; tax exemptions; grants, loans, and bailouts at taxpayer expense; laws that protect them from competition; laws that force people to buy their products; and much more. All of these come with the threat of force implicit in everything governments do.

Money is taken from one and given for the exclusive use of another. Laws are imposed upon one in order to benefit another. We find this distasteful, and rightly so.

The Pareto Problem

The Pareto Distribution is a fact of life. In many areas of human endeavor, a small number of people have more. More fame. More followers. More talent. More money.

And a tiny number will have A LOT more.

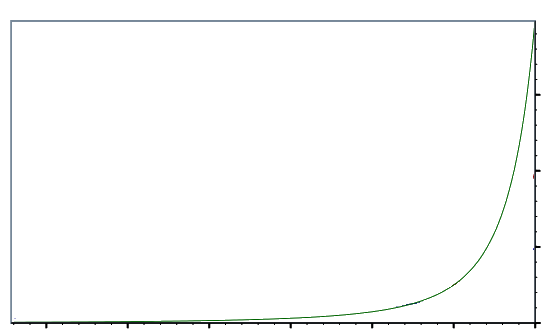

The phenomenon is self-reinforcing. Talent produces followers and fans. This leads to fame, which creates more fans. Fans spread the word and this brings in more fans. The whole thing snowballs and you end up with a tiny number of people being super-famous, a small number being sorta-kinda famous, and then…everyone else.

The same thing happens with money. If you have enough money, you can use that money to make investments to grow more money. And more and more. The phenomenon is geometric. The rich really do get richer. People talk about the 1 percent and the 99 percent, but the geometric progression is such that most of the wealth isn’t held by the 1 percent, it is held by the .01 percent.

This is a species-wide problem, and we don’t know how to deal with it. Indeed, there appears to be no way to deal with it without massively restricting freedom. People are unequal in talents, drive, and natural endowments. Some are going to get richer, more famous, more airplay, more fans—and then the Pareto phenomenon is going to raise a tiny portion of that number to unimaginable heights.

And short of some sort of Harrison Bergeron scenario, there is not much we can do about it—other than constantly trying to use violence to level the playing field.

Fiat Currency

When money was an agreed-upon means of exchange whose value was determined by a free market (by millions of voluntary decisions by free people), it was a useful and necessary tool. The government officials got involved.

At first, they arrogated the production of “legal” currency, but at least the currency was something real: gold, silver, or other things people deem precious. Then rulers and government officials discovered that they could get more money for themselves if they debased the coinage—mixing the precious metals with less precious ones.

Eventually, the need to back currency with a real commodity, even a debased one, turned out to be too much of an impediment, so governments turned to fiat money. In essence, they print the money, make an entry in a ledger saying the money exists, and poof—it exists. It is tantamount to a legal counterfeiting operation.

This is the cause of inflation—one of the cruelest taxes of all. Gold remains just as intrinsically valuable as it always was, but in the fiat currency of, say, the United States, its value has gone from $20 to $3,000 for an ounce. In other words, the value of US fiat currency has cratered.

Even those of us who do not know what causes inflation know that it is bad. They know that a loaf of bread that used to cost a nickel now costs 100 nickels. Fiat currency makes money feel all the more…wrong.

You Can’t Take It With You

The Valley of the Kings in Egypt is filled with tombs. Those tombs are filled with gold and silver and chariots and fabulous wealth, and with the mummies of pharaohs who tried to take the wealth with them. And yet they are just as dead and gone as the ‘lowliest’ peasant.

We know this. We may pretend we don’t, especially when we’re young, but we know. And we don’t like it.

All the money in the world can’t prevent the inevitable. Part of us may resent money for that—especially since we have to spend so much time working for it throughout our lives. But a bigger part recognizes that as helpful as money can be, there are far more important things in life.

As the song says, “You can’t buy a ticket to the Pearly Gates.”

And here are three appropriate songs on the subject, for #FreedomMusicFriday!

On the recommendation of

, I am adding this:

How much is too much? Most people would say any amount is OK if it’s mine. If we’re talking fiat paper, the answer should be the opposite. ANY amount is too much, anywhere, at anytime.

And so much for wishful thinking.

Not one of my favorite ABBA songs, but bearable. The strange thing about money is that you only rent it for a short time. You do not own it, it owns you. If you have a whole lot, you need to constantly protect it. If you have little, you need to constantly earn more to survive.

It is perhaps a decent medium of exchange for any transaction but go ahead and have your millions or billions (if you have that much) stuffed into your coffin for the next life.

So you get to the gates of Heaven or Heck and all they take are green stamps. I should ask my wife...maybe they give you a clue in the Bible.